The Pandemic Calls for Critical Changes in How We Design Cities

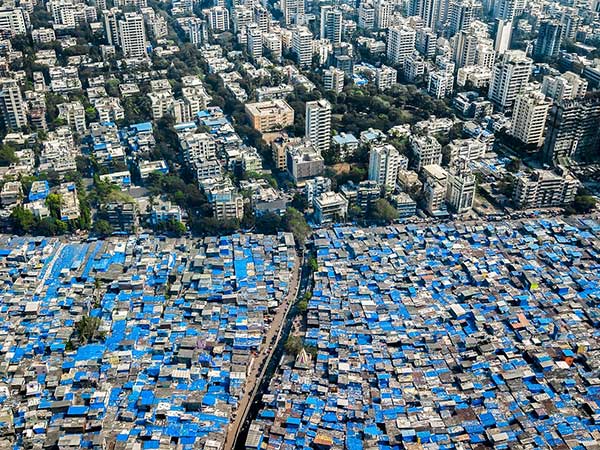

The COVID-19 crisis has brought to the forefront the shortcomings of metropolises and megacities across India. In densely populated cities of India, as city administrations struggle to adapt to social distancing norms, the dynamics of urban life have had to be reimagined, albeit temporarily. As a result, we’ve seen conventional ways of living and socializing transformed drastically over a period of just a few months.

Among the many lessons the pandemic has taught us, the most significant one is the realization of the difference between what we need and what we desire. Broadly speaking, our essentials include access to clean air and water for health and wellbeing; fresh food and vegetables available regularly within walking distance; civic security; affordable and effective healthcare services available locally; assistance for cleaning and maintenance of community spaces; and lastly, the ability to interact with local representatives to ensure the availability and progressive improvement of the said public services.

One immediate solution to achieve these essentials within a large city could be to revise urban policies to allow for neighbourhood planning and governance to decentralise decision-making to the neighbourhood level and enabling a bottom-up approach to budget-making. Existing wards in Indian metropolises like Mumbai are too expansive for planning effective neighbourhoods, so the first step would be to restrict the area of a neighbourhood unit, by definition, to approximately one square kilometre.

They could then evolve over 10-20 years based on prioritised community needs to become self-sustaining units with all public facilities and amenities available locally from better-designed schools and hospitals to gardens to spaces for weekly farmer markets and waste segregation and recycling; units that can be administered with ease and where inhabitants would be able to walk or cycle to work, to school, to shop, and to play. This would reduce the need for regular inter-neighbourhood travel, and by corollary, the high levels of carbon emissions and pollution in our cities today. This principle would percolate to the smallest element of the unit as well. For instance, an apartment complex could have 10% space reserved on site with small, 300-350 square-feet rooms or apartments to accommodate all staff that works within the complex (security guards, drivers, cleaning or cooking maids etc.) and their families.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given us a lot to think about. And while we tackle the short-term problems it has presented, it’s equally important to ensure that long-term solutions are put in place so our cities and infrastructural systems become resilient to socio-economic disruptions –– so our future is more secure, liveable, and sustainable.